From 3-14 March, the Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) is holding their Conference of Parties 16 (CoP16) in Bangkok, Thailand. While some species will get the protection they so desperately need to survive in the wild, others seem to fall by the wayside. What constitutes a species being placed on the coveted Appendix I list? Is a down listing to Appendix II or III, or a delisting a death sentence for species? Do CITES regulations really help protect endangered species or simply pay lip service to the angry mob?

From 3-14 March, the Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) is holding their Conference of Parties 16 (CoP16) in Bangkok, Thailand. While some species will get the protection they so desperately need to survive in the wild, others seem to fall by the wayside. What constitutes a species being placed on the coveted Appendix I list? Is a down listing to Appendix II or III, or a delisting a death sentence for species? Do CITES regulations really help protect endangered species or simply pay lip service to the angry mob?

A great deal of confusion surrounds what CITES is and their limitations within the realm of wildlife conservation. First and foremost, CITES sets only trade agreements between countries regarding wildlife and their parts; this act is in no way a conservation or biodiversity agreement. In addition, there is no regulation within a country, only between countries. There are currently 190-200 countries that makeup CITES. Member countries are required to enforce the agreements within their own countries as CITES itself does not have a task force or any agency within to monitor trade or enforcement of trade regulations.

At the CoP16, species are voted to be included on one of three lists: Appendix I, II, or III. Under Appendix I, all commercial trade is banned for these species as they are deemed at a high risk of extinction due to overexploitation. A caveat is that taking these animals in noncommercial trade including scientific research is still allowed. Appendix II species are at risk of becoming extinct if international trade is not regulated and monitored. Thus, trade in those species listed on Appendix II requires an export permit. Appendix III species are not considered rare on a global scale, but long-term survival is of extreme concern within a few home countries. A certificate of origin is required for trade in Appendix III species. At present, there are 600, 1400, and 270 species listed on Appendices I, II, and III, respectively.

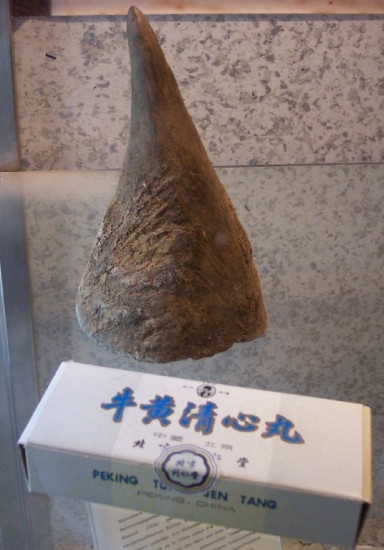

There are more then a few conservationists who think that CITES species listings, and subsequent  regulations, are not as clear and defined as they should be to protect at risk species. A great example of this type of muddled regulation is the rhino. Currently, we are in the midst of a poaching crisis. Rhino are being killed at an alarming rate for their horns. Since all species of rhino are endangered, one would think they should be a top priority on Appendix I. Although rhinos are endangered globally, their wild populations within a few countries are thriving. In such countries as South Africa and Swaziland, rhino population management has been heavily funded to ensure a successful breeding program to fuel the trophy hunting industry. Unfortunately, in these countries, rhinos have been down listed to Appendix II with some concern of a further drop to Appendix III. Can this type of regulation help or ultimately hinder conservation efforts?

regulations, are not as clear and defined as they should be to protect at risk species. A great example of this type of muddled regulation is the rhino. Currently, we are in the midst of a poaching crisis. Rhino are being killed at an alarming rate for their horns. Since all species of rhino are endangered, one would think they should be a top priority on Appendix I. Although rhinos are endangered globally, their wild populations within a few countries are thriving. In such countries as South Africa and Swaziland, rhino population management has been heavily funded to ensure a successful breeding program to fuel the trophy hunting industry. Unfortunately, in these countries, rhinos have been down listed to Appendix II with some concern of a further drop to Appendix III. Can this type of regulation help or ultimately hinder conservation efforts?

Within the first week of the CoP16, several species have gained support for conservation through trade bans. The ban in the trade of sharks is a huge step in the eradication of the cruel act of shark finning. Shark populations have plummeted as the demand for shark fins for soup and use in Ancient Chinese Medicine has soared. However, where some species gain support others do not. Despite a great push to stop the global trade of rhino horn, regardless of in country populations, the motion was voted down. It has been reported that scientific data support a controlled rhino horn market to relieve poaching pressure. This model was based upon the success of crocodile farming to diminish numbers of animals illegally taken from the wild. Conversely, tiger farming and bear bile farms, working from this same premise, have done nothing to help alleviate poaching of wild populations and in some instances caused an increase in the cruel act. Wild animals are thought to be more “pure” then farmed counterparts. Tigers and bears are still taken from the wild for their parts at numbers that threaten their very existence.

Within the first week of the CoP16, several species have gained support for conservation through trade bans. The ban in the trade of sharks is a huge step in the eradication of the cruel act of shark finning. Shark populations have plummeted as the demand for shark fins for soup and use in Ancient Chinese Medicine has soared. However, where some species gain support others do not. Despite a great push to stop the global trade of rhino horn, regardless of in country populations, the motion was voted down. It has been reported that scientific data support a controlled rhino horn market to relieve poaching pressure. This model was based upon the success of crocodile farming to diminish numbers of animals illegally taken from the wild. Conversely, tiger farming and bear bile farms, working from this same premise, have done nothing to help alleviate poaching of wild populations and in some instances caused an increase in the cruel act. Wild animals are thought to be more “pure” then farmed counterparts. Tigers and bears are still taken from the wild for their parts at numbers that threaten their very existence.

When we take CITES for exactly what it is, a trade agreement, we can see that it does what it has set out to do. CITES sets global trade agreements according to wild populations. Yet, how much can trade agreements actually do to help endangered wildlife? At the end of the day regulation comes down to individual countries to regulate and monitor what happens within and across their boarders. At present, it does not appear that any regulation exists at all. The increase in illegal trade of ivory, rhino horn, tiger parts, pangolins, great apes, etc., shows a regulatory system that is failing. I do believe that CITES is laying a strong foundation for regulation to be enforced by others, but the lack of protection and enforcement will prove to be the ultimate demise of some of our most iconic species. Why do animals need to be placed on a list in order to be protected? Can we not exercise common sense and compassion to see that global demand for wildlife will inevitably be the death of us all?