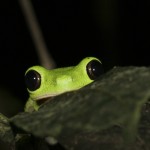

Recently, I had the privilege of spending time with a biologist studying the impact of the chytrid fungus on amphibian populations, as well as some of the beautiful Panamanian Golden Frogs (Atelopus zeteki) in her study. Chytrid is a type of fungus that is exclusively found in water or in moist environments. Although there are over 1,000 identified chytrid species it is the Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis that has been traversing the globe decimating amphibian populations. First identified in 1998, the B. dendrobatids species of chytrid has been found to infect the skin of amphibians; infection causes the skin to thicken. The microscopic changes in skin integrity are specifically detrimental to amphibians because they use their skin as one of three respiratory surfaces. The thickening of the skin thus interferes with electrolyte balance, oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange, and proper function of the circulatory and respiratory systems resulting in death. Via

Recently, I had the privilege of spending time with a biologist studying the impact of the chytrid fungus on amphibian populations, as well as some of the beautiful Panamanian Golden Frogs (Atelopus zeteki) in her study. Chytrid is a type of fungus that is exclusively found in water or in moist environments. Although there are over 1,000 identified chytrid species it is the Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis that has been traversing the globe decimating amphibian populations. First identified in 1998, the B. dendrobatids species of chytrid has been found to infect the skin of amphibians; infection causes the skin to thicken. The microscopic changes in skin integrity are specifically detrimental to amphibians because they use their skin as one of three respiratory surfaces. The thickening of the skin thus interferes with electrolyte balance, oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange, and proper function of the circulatory and respiratory systems resulting in death. Via epidemiological studies, it has been discovered that the chytrid epidemic is responsible for the death of millions of frogs worldwide and the wild extinction of over 100 species including the Panamanian Golden Frog. An important side note is that not all amphibian species infected become sick and die. For example the American bullfrog and African clawed frog has been identified as species that are resistant the chytrid. These species are particularly dangerous as they act as carriers of the disease.

epidemiological studies, it has been discovered that the chytrid epidemic is responsible for the death of millions of frogs worldwide and the wild extinction of over 100 species including the Panamanian Golden Frog. An important side note is that not all amphibian species infected become sick and die. For example the American bullfrog and African clawed frog has been identified as species that are resistant the chytrid. These species are particularly dangerous as they act as carriers of the disease.

It was not immediately known how chytrid become so widely spread. To date chytrid has been found in both wild and captive amphibian populations on every amphibian-inhabited continent; chytrid has been detected on 350 species of amphibians in 43 countries. At first scientist suspected that changes in the environment may have caused immune system suppression in amphibians allowing them to become  susceptible to chytrid infections. However, it has since been determined that the specific chytrid that infects amphibians is an introduced, non-native species. Although an exact site of origin has not been defined, it is well-known that chytrid has been present in Africa, Japan, and Eastern America for a long time with many chytrid-resistant amphibian species found in these areas. In addition, there is mounting evidence that the high demand for the global trade of amphibians as pets, food, on display at zoos, or use in laboratories is responsible for the introduction of chytrid into non-chytrid areas. The most common routes of infection is by direct animal to animal contact, on people’s shoes or belongings as they move from one environment to another, and on birds or winged insects.

susceptible to chytrid infections. However, it has since been determined that the specific chytrid that infects amphibians is an introduced, non-native species. Although an exact site of origin has not been defined, it is well-known that chytrid has been present in Africa, Japan, and Eastern America for a long time with many chytrid-resistant amphibian species found in these areas. In addition, there is mounting evidence that the high demand for the global trade of amphibians as pets, food, on display at zoos, or use in laboratories is responsible for the introduction of chytrid into non-chytrid areas. The most common routes of infection is by direct animal to animal contact, on people’s shoes or belongings as they move from one environment to another, and on birds or winged insects.

For resistant species, chytrid presence on the skin is undetectable. However, for non-chytrid-resistant species clinical signs of infection appear as a discoloration or in most cases a reddening of the skin, abnormal behaviors and excessive shedding of the skin. Because of the number of biological mechanisms that chytrid interrupts, a wide variety of symptoms due to infection have been documented; unfortunately, chytrid symptoms are the same for other amphibian disease and is therefore often times not discovered until postmortem.

discoloration or in most cases a reddening of the skin, abnormal behaviors and excessive shedding of the skin. Because of the number of biological mechanisms that chytrid interrupts, a wide variety of symptoms due to infection have been documented; unfortunately, chytrid symptoms are the same for other amphibian disease and is therefore often times not discovered until postmortem.

Within captive populations administration of antifungal medication along with disinfection of contaminated enclosures has been successful in chytrid treatment; however, in the wild the captive treatment regimen is not feasible. In wild populations it is impossible to maintain the concentration of antifungal medication needed to successfully treat infected individuals, as well as disinfect the natural environment. Although the future of chytrid infected susceptible species seem bleak, researchers refuse to give up hope. Just this week in the news zoologist at Oregon State University revealed they have discovered a type of zooplankton, Daphnia magna, which eats the chytrid fungus.

Within captive populations administration of antifungal medication along with disinfection of contaminated enclosures has been successful in chytrid treatment; however, in the wild the captive treatment regimen is not feasible. In wild populations it is impossible to maintain the concentration of antifungal medication needed to successfully treat infected individuals, as well as disinfect the natural environment. Although the future of chytrid infected susceptible species seem bleak, researchers refuse to give up hope. Just this week in the news zoologist at Oregon State University revealed they have discovered a type of zooplankton, Daphnia magna, which eats the chytrid fungus.

Once again it is imperative to understand how human actions cause global disruptions and even collapse of fragile ecosystems. Were it not for the global distribution of amphibians for human needs, chytrid would not have been introduced into naïve habitats causing the annihilation of local amphibian population. I cannot stress enough the need for all of us to be responsible consumers. Regardless if we are legally or illegally consuming animals for food, using animal parts medicinally and ornamentally, or obtaining animals as pets, our demand effects the environments from which the animal is leaving and entering. This is especially true in cases where non-native pets are released into new environments.

global distribution of amphibians for human needs, chytrid would not have been introduced into naïve habitats causing the annihilation of local amphibian population. I cannot stress enough the need for all of us to be responsible consumers. Regardless if we are legally or illegally consuming animals for food, using animal parts medicinally and ornamentally, or obtaining animals as pets, our demand effects the environments from which the animal is leaving and entering. This is especially true in cases where non-native pets are released into new environments.

For more information on chytrid and its effects on amphibian population please visit www.savethefrogs.com and www.amphibainark.org

For more information on chytrid and its effects on amphibian population please visit www.savethefrogs.com and www.amphibainark.org