The Timber Rattlesnake

Crotalus horridus

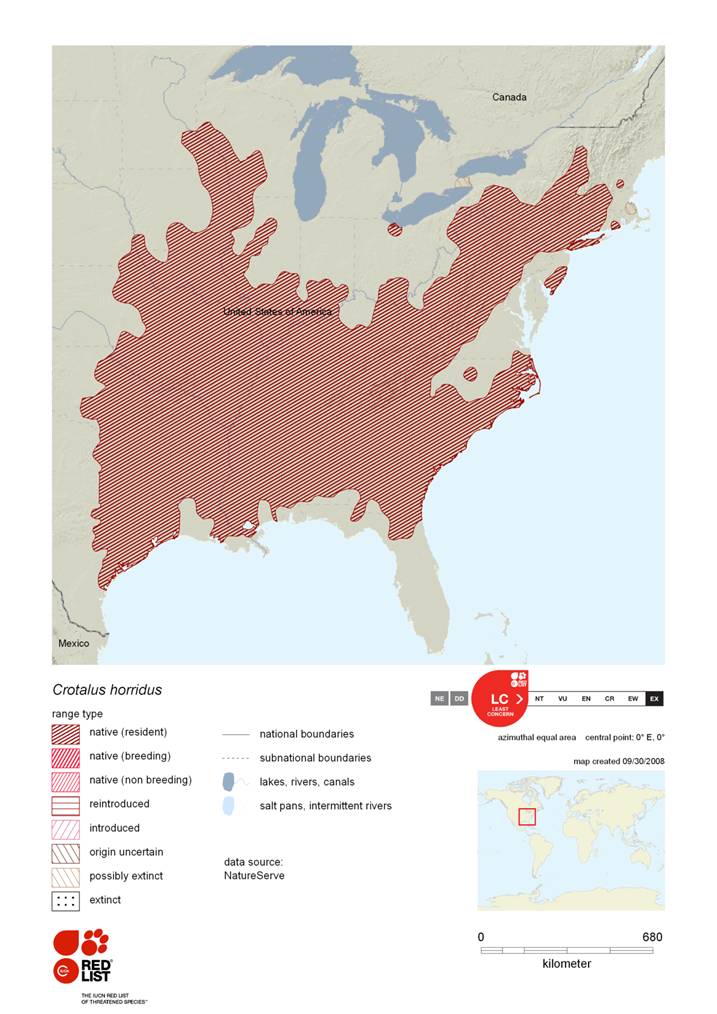

The timber rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus) is one of 29 species of rattlesnake living throughout the Americas. Although the name insinuates something horrifying, literally, the timber rattlesnake is a secretive and passive keystone species keeping the ecosystem in check as both predator and prey. Listed as least concern to near threatened throughout its wide range by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), differing color variations of the timber rattlesnake can be found from Ontario, Canada, Southern Minnesota, East Texas, and Northern Florida to Maine, United States. Timber rattlesnakes have a diverse habitat and can be found in deciduous forests among felled trees and rocky outsroppings to lowland swamps. While the size of the North American population of the timber rattlesnake is unknown, numbers are thought to exceed 100,000. It is acknowledged by the IUCN that the overall population trend is decreasing (Hammerson, 2007).

Although the name insinuates something horrifying, literally, the timber rattlesnake is a secretive and passive keystone species keeping the ecosystem in check as both predator and prey. Listed as least concern to near threatened throughout its wide range by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), differing color variations of the timber rattlesnake can be found from Ontario, Canada, Southern Minnesota, East Texas, and Northern Florida to Maine, United States. Timber rattlesnakes have a diverse habitat and can be found in deciduous forests among felled trees and rocky outsroppings to lowland swamps. While the size of the North American population of the timber rattlesnake is unknown, numbers are thought to exceed 100,000. It is acknowledged by the IUCN that the overall population trend is decreasing (Hammerson, 2007).

Not as big as the 96 inch long Eastern Diamondback rattlesnake, the Timber rattlesnakes averages 39.8-59.8 inches in length. Much about the physiology of this species depends on location and prey availability. In southern, warmer areas the timber rattlesnake tend to be bigger, reach puberty at a younger age, and reproduce more frequently. In comparison, it is thought that the northern timber rattlesnake achieves sexual maturity between 8 to 12 years of age and has a litter every 3 to 5 years to 5 to 15 young (Brown, 1992 and 1993). By comparison, the male reaches sexual maturity at 6 years of age (Brown, 1995). This is extremely important from a conservation standpoint in that it is not easy for the timber rattlesnake to increase its population rapidly. Furthermore, the average lifespan of the timber rattlesnake in the wild is approximately 20 years; a healthy female may reproduce only three to four times her entire life.

Timber rattlesnakes, like all rattlesnakes, are ovoviviparous meaning they retain their eggs internally during gestation and give birth to live young. Although the mating season occurs during late July to early August, it is thought that the sperm in kept viable as the female overwinters in her den and fertilization does not take place until the following spring and parturition the following fall 1 year after mating.

The main diet of the timber rattlesnake consists primarily of small mammals, i.e., chipmunks, voles and squirrels. However, there have been observations of timber rattlesnakes also feeding on other snakes, amphibians and  birds. Regardless of prey, timber rattlesnakes are ambush predators. Using heat-sensing pits situated around their nose and mouth, and a highly developed sense of taste, timber rattlesnakes can strike prey in a split second. Utilizing a bite and release hunting style, the timber rattlesnake will envenomate its prey upon first strike, release it, and wait for its meal to die (Clark, 2002). Rattlesnake fangs are like two hypodermic needles able to deliver a large venom yield with every bite. Venom can be a mix of a neuro- and hemotoxin.

birds. Regardless of prey, timber rattlesnakes are ambush predators. Using heat-sensing pits situated around their nose and mouth, and a highly developed sense of taste, timber rattlesnakes can strike prey in a split second. Utilizing a bite and release hunting style, the timber rattlesnake will envenomate its prey upon first strike, release it, and wait for its meal to die (Clark, 2002). Rattlesnake fangs are like two hypodermic needles able to deliver a large venom yield with every bite. Venom can be a mix of a neuro- and hemotoxin.

There are a variety of threats to the longevity of the timber rattlesnake. Habitat destruction creates a serious problem to rattlesnake dens and hunting areas. Timber rattlesnakes are not drawn to forest areas that have been clear cut. In addition, clearing cutting forest is usually synonymous with changing forest landscape. Den areas in rocky outcrops are disturbed and destroyed, detrimental to a species that reuses the same den site annually. By disturbing timber rattlesnake den sites it causes the snakes to move and potentially come into conflict with humans. Habitat disruption and destruction also has the potential to lead to road mortalities by vehicle on highways and ATV or trails.

The intentional collection and/or killing of the timber rattlesnake is another primary threat to this species. Rattlesnake round-ups are help under the guise of protecting humans and domestic animals from their potentially deadly strike. In addition, the rattlesnake is highly sought after in the illegal pet trade by reptile collectors and for display at roadside zoos. Regardless, whether death or collection, rattlesnakes are removed from their environment resulting in an unbalanced ecosystem.

References

Brown, W.S. 1992. Emergence, ingress, and seasonal captures at dens of northern Timber Rattlesnakes, Crotalus horridus. In: Campbell, J.A., Brodie, E.D. (Eds). Biology of Pitvipers. Selva, USA. Pp. 251-258.

Brown, W.S. 1993. Biology, status, and management of the Timber Rattlesnakes (Crotalus horridus): A guide for conservation. SSAR, Oxford, Ohio.

Brown, W.S. 1995. Heterosexual groups and the mating season in a northern population of Timber Rattlesnakes, Crotalus horridus. Herptological Natural History 3:127-133.

Clark, R.W. 2002. Diet of the Timber Rattlesnakes, Crotalus horridus. Journal of Herpetology. 36:494-499.

Hammerson, G.A. 2007. Crotalus horridus. In: IUCN 2011. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.1. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Accessed 03 August 2011.